Abroad, our nation is committed to an historic, long-term goal: We seek the end of tyranny in our world. Some dismiss that goal as misguided idealism. In reality, the future security of America depends on it. (...) In all these areas -- from the disruption of terror networks, to victory in Iraq, to the spread of freedom and hope in troubled regions -- we need the support of our friends and allies. To draw that support, we must always be clear in our principles and willing to act. The only alternative to American leadership is a dramatically more dangerous and anxious world.The inclusion of the "Long War" as a cornerstone concept into the SotU speech gives a special weight to its place in the QDR. The exact role and definition within the military grand strategy perspective remains to be seen, but what it does already do now, is to offer common grand strategy framework which in many ways is not only, as mentioned in the speech, bipartisan in the American context, but also in principle in the transatlantic, wider left-right context. All of the questions about use of force, when to use it, and who gets to decide will stay with us for along time -- but what we basically have here is a continuation of the realignment between the "tough" and "soft" parts of global international politics. Bushs vision offers a two-pronged refusal of isolationism (the only thing Europeans secretly fear more than "blundering US activism") and a further, more deep-reaching convergence between security and development:

Yet we also choose to lead because it is a privilege to serve the values that gave us birth. American leaders -- from Roosevelt, to Truman, to Kennedy, to Reagan -- rejected isolation and retreat because they knew that America is always more secure when freedom is on the march. Our own generation is in a long war against a determined enemy, a war that will be fought by presidents of both parties who will need steady bipartisan support from the Congress. And tonight I ask for yours. Together, let us protect our country, support the men and women who defend us, and lead this world toward freedom.

Our offensive against terror involves more than military action. Ultimately, the only way to defeat the terrorists is to defeat their dark vision of hatred and fear by offering the hopeful alternative of political freedom and peaceful change. So the United States of America supports democratic reform across the broader Middle East. Elections are vital, but they are only the beginning. Raising up a democracy requires the rule of law, and protection of minorities, and strong, accountable institutions that last longer than a single vote. (...) Democracies in the Middle East will not look like our own, because they will reflect the traditions of their own citizens. Yet liberty is the future of every nation in the Middle East, because liberty is the right and hope of all humanity. (...)An important piece of the Bush administration's development policy was to be the -- so far disappointing -- Millennium Challenge Account, administered by the Millennium Challenge Corporation, with a promised budget of 5 billion dollars annually. The simple and promising idea behind the MCC was to award development aid to countries that was already showing progress towards democratic and accountable reform, and then to give larger, more targeted funding. By creating incentives for more efficient, democratic and accountable state-building instead of focusing on purely need-based evalutations the MCC would then "invest" in the "democratic growth stocks" of the developing world. The MCC had a very bad run in the beginning, took too long to set up, and started extremely slowly in disbursing aid: these problems are now being addressed according to this interview with the new director in the Washington Post. The US may in this way be on its way to be a significant policy innovator in the realm of output based aid -- new public management for development policies -- if not in absolute ODA (Official Development Assistance) terms.

To overcome dangers in our world, we must also take the offensive by encouraging economic progress and fighting disease and spreading hope in hopeless lands. Isolationism would not only tie our hands in fighting enemies; it would keep us from helping our friends in desperate need. We show compassion abroad because Americans believe in the God-given dignity and worth of a villager with HIV/AIDS, or an infant with malaria, or a refugee fleeing genocide, or a young girl sold into slavery. We also show compassion abroad because regions overwhelmed by poverty, corruption and despair are sources of terrorism and organized crime and human trafficking and the drug trade. In recent years, you and I have taken unprecedented action to fight AIDS and malaria, expand the education of girls, and reward developing nations that are moving forward with economic and political reform. For people everywhere, the United States is a partner for a better life. Short-changing these efforts would increase the suffering and chaos of our world, undercut our long-term security and dull the conscience of our country. I urge members of Congress to serve the interests of America by showing the compassion of America.

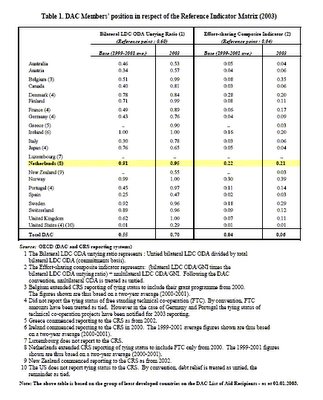

Two challenges are paramount for the MCC to deliver substantially: to introduce this kind of condition-based aid without losing focus on the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and to square this aim of choosing reform-willing partner countries with the OECD's DAC Guidelines on ODA in terms of effective focus on poverty reduction. One important element of the latter is the untying of aid, i.e. scrapping demands for procurement in donor countries. Untying development aid may be the development world's equivalent of agricultural subventions in that it effectively hampers growth of recipient countries' own capacities. According to the OECD there is some, but modest progress on this area: only 13% of overall ODA was untied in 2003. The ratio of LDC ODA that was untied (to tied LDC ODA) has risen substantially across the board for most DAC member countries since the Guidelines where agreed upon in 2001 (click picture for enlargement; page 14 of link above).

The Long War is thus not only a Pentagon affair, and it cannot be: the convergence of security and development means that both elements, seperately and jointly, have to deliver for the results to emerge. Whether the MCC -- including the USAid threshold program -- will be an efficient player in that game will depend among other things on its ability to deliver on poverty reduction in the LDCs.

No comments:

Post a Comment